“History of Defence Movement: Victoria’s First Soldiers by A.W. Greig”

This history was published on 6th April 1912 in the Melbourne newspaper, the Argus. The article is long, and the print faded, so I will transcribe it in installments. The punctuation, spelling, and lengthy sentences are as printed. I have added some contemporary illustrations, as well as those included with the article. I found it interesting; I hope you do too.

_____________________

Part 4

The year 1870 saw an event of some importance in the military history of Victoria. It had been for a long time realised that there was a possibility of the Imperial troops being withdrawn, just when their services were most required. In 1860 a temporary withdrawal had, in fact, taken place in connection with the Maori war in New Zealand, and garrison duty had for a time devolved upon the volunteer force. In June, 1863, the home Government definitely intimated that the protection afforded to Australia would be mainly naval, and that the raising of land forces must be left to the colonists themselves. Imperial troops would still be stationed here, but it would be “impossible for Her Majesty’s Government to guarantee, under all circumstances, a definite number of troops.” There was no mistaking the meaning underlying this sentence, and in Victoria objection, was not unnaturally taken to being saddled with the burden of maintaining troops in a time of peace, only to have them withdrawn in time of war. Negotiations proceeded on the subject for some time, and were finally brought to a conclusion in 1869, when the British authorities were plainly informed that Victoria would not continue to maintain Imperial troops, unless guarantees were given that these should remain in the colony in war-time, as well as during peace, and should further consist of artillery, instead of infantry. The result of this ultimatum was the withdrawal of the British soldiers, the last of whom left on August 21, 1870. Immediately after their departure steps were taken to form a small force of permanent artillery to man the harbour and costal defences.

Between 1864 and 1875 the volunteer force maintained a fair average of three to four thousand members, and in the latter year the Lancaster rifle was superseded by the Martini Henry; but in the late seventies and early eighties we find distinct signs of decadence. The investigations of Parliament in March 1876, revealed grave defects in the existing legislation affecting defence matters. There was no compulsory period of service for volunteers – the whole force, or any portion of it, could disband itself at fourteen days’ notice nor could attendance at drills be enforced. Veteran officers referred regretfully to the early days of the movement, when “the ranks were filled with men of wealth and position,” and “parades and drills at daybreak and late at night were unceasing,” a practice so far departed from that at the period of the report “daylight drills were almost totally neglected. Little regard seems to have been paid by the military authorities to climatic conditions in prescribing the uniform to be worn, and we find the captain of the East Melbourne Artillery confessing that he had been deterred from attending parades in the hot weather on account of the costume he was expected to wear.

State Library Victoria # 9931878603607636. Mr G. Bruce of the East Melbourne artillery. 1866. His busby is located on the stand to the left.

Military traditions decreed that the artilleryman in full dress should crown his unfortunate head with a busby and for those corps whose aspiration did not lead them to completeness in this respect there was no alternative but the forage cap, which latter, even supplemented by a white “puggaree,” afforded no protection whatever to the face. (ED: a pugaree is a folded cloth band.)

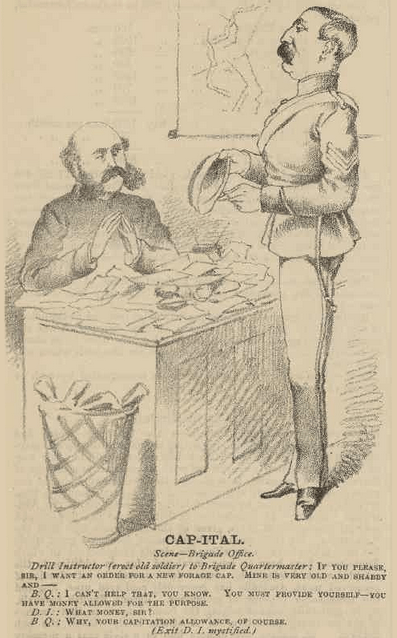

Sydney Punch, 31st October 1872, page 3.

1872 illustration of a shako.

Slightly more reasonable was the “shako” worn by riflemen, which was a cap closely resembling our present-day (Ed: 1912) letter carriers. It was not until April, 1875, that a military board recommended the adoption of a light helmet as the summer headdress of the artillery.

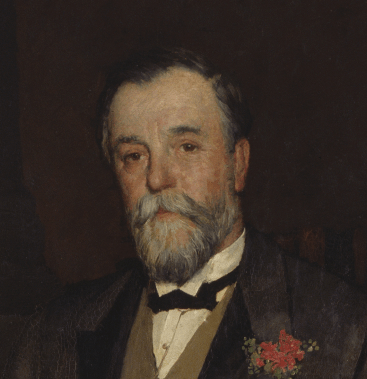

No active steps were taken for some years to remedy the state of affairs, and the volunteer force continued to go steadily down the hill, the defects arising from lack of enthusiasm among its members being aggravated, according to the contemporary press, by “unfair treatment and neglect” on the part of the authorities. In 1881 it was asserted that the guns of the Metropolitan Artillery Corps had not fired a shot or shell for about three years, the reason being that those corps who spent money on ammunition for target practice were stinted in other directions in consequence. Review attendances fell from 2,700 in 1876 to 1,700 in 1883, and by the end of the latter year the full strength of the volunteer force was only about 2,500. By this time, however, Parilament had at last been persuaded by the first Minister of Defence (Sir Frederick Sargood) to put into effect a recommendation which had been made from a dozen different sources during the preceeding 25 years, and to authorise the enrolment of a paid militia.

State Library of Victoria: Detail from 1897 portrait of Sir F. Sargood.

Under a scheme prepared by Sir Frederick, who had been a member of the volunteer force since 1859, a Council of Defence was formed, and entrusted with the gradual disbandment of the volunteers, and the enrolment of militias in their place. The old system rapidly disappeared, and by June 30, 1885, the number of citizen soldiers enrolled under the more stringent, but, at the same time, more businesslike arrangement, had risen to over four thousand five hundred.

http://www.austbuttonhistory.com/1st-november-2020/

http://www.austbuttonhistory.com/29th-october-2020/

For any comments or questions, please use the Contact page.